Given the state of the world at the time of this writing, I’d much rather be doing an exhibition of frayed knots or whatever. But on the other hand, I guess there’s no time like the present to remember that war is absolute bullshit. And anyway, this exhibit is pretty great and very well done.

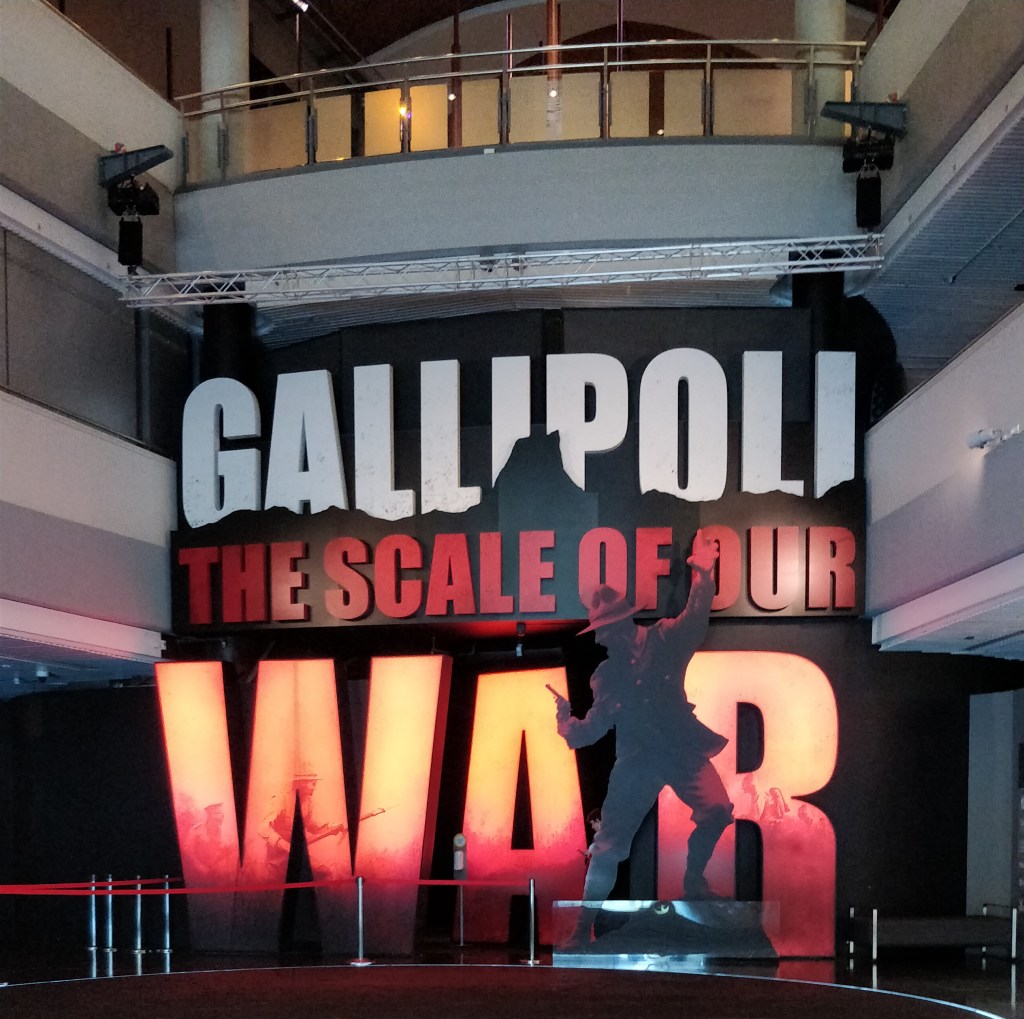

Te Papa, the national museum of New Zealand, will definitely get its own entry eventually. It’s very large and hosts pretty grand temporary exhibitions. The Scale of Our War is technically not permanent, but it is still a few years from the end of its run (2015 to 2025) and it is very grand. The figures that anchor each section are 2.4 times life size and were created by local prop maker Weta Workshop. Maybe you’ve heard of them.

The history of World War I is complicated and brutal and well worth reading about, especially if you’re looking to really trace how exactly a conflict that resulted in so much devastation and death could feel both entirely preventable and wholly inevitable. It was a blood-soaked baptism into the modern age. There are many horrific parts to the whole thing–Ypres, the Somme, the Argonne, etc etc etc–but for New Zealand and Australia, Gallipoli looms largest.

I won’t try to lay out the ebbs and flows of the campaign, because it was eight months of hell spent in service of trying to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war, and it absolutely did not work. It started with a bad landing, continued with failed offensives, and ended in an evacuation when command decided there were better positions to die for in Europe. The Allies lost 44,000 lives. The Ottoman Empire lost 87,000. It made little difference to the wider war–but it helped shape the national identities of Australia, New Zealand, and Turkey.

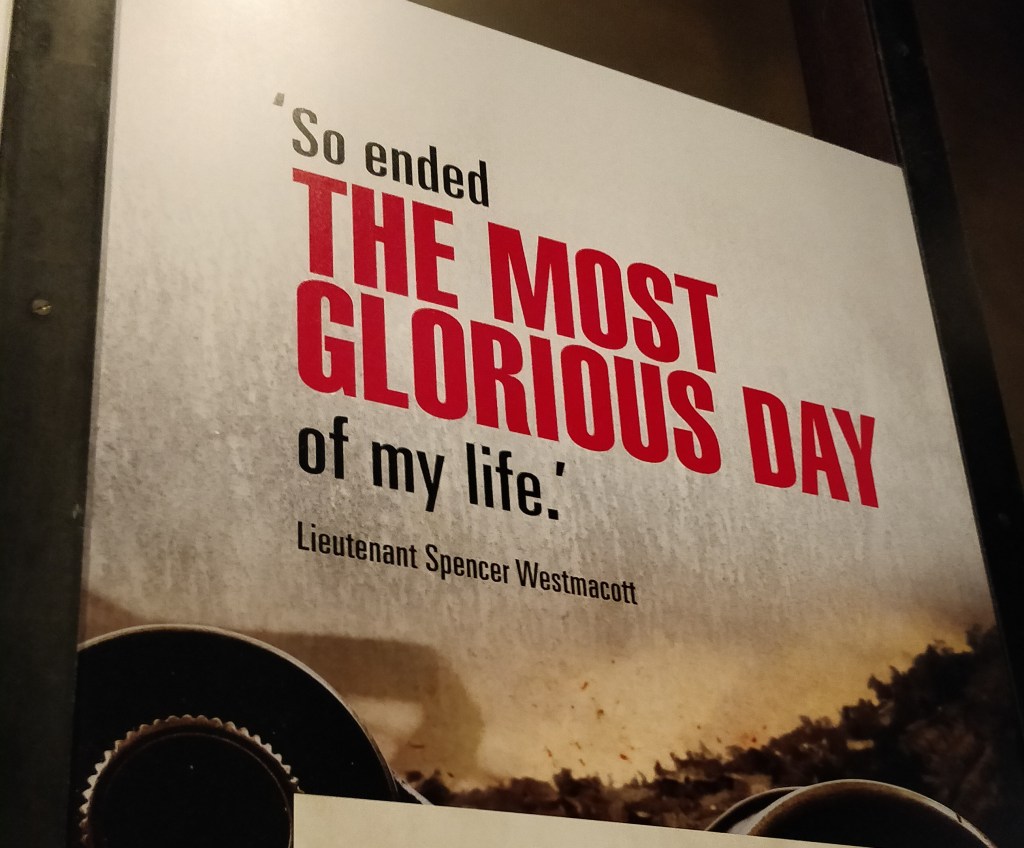

The exhibit includes overviews of the campaign as well as the stories of eight New Zealanders, who are depicted by those very large statues. It’s an effective way to hook the audience into a dense topic. You start with Lt. Spencer Westmacott.

Westmacott would land at Gallipoli on April 25, sustain wounds that would cost him his right arm, and be evacuated that night. His feelings about his experience there reminded me of the narrations in They Shall Not Grow Old, where many soldiers spoke fairly warmly of their time at the front.

The space of the exhibit is laid out pretty well, in my opinion. You follow the line, which not only helps the flow of traffic but also guides you through with a sense of how time was passing during the campaign.

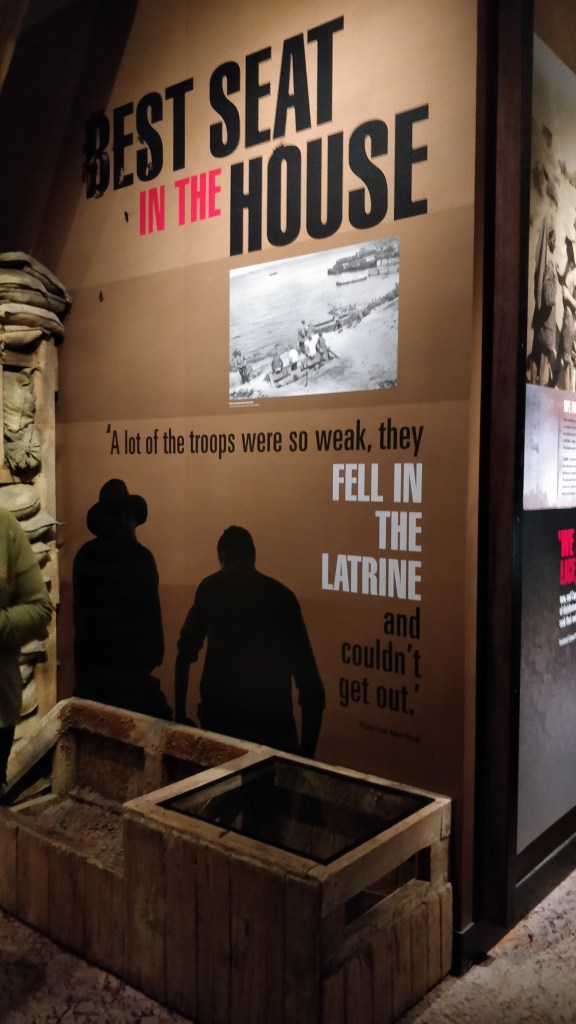

As I mentioned, I’m not going to go through the details of story here–for one thing, this post has been in drafts for some months and I currently have covid; for another, I’ve already linked to one good overview–but I have a lot of admiration for a history-based museum exhibition that does a solid job of engaging the patron. History can be tough for engagement, as it tends to be text-dense, rely on not-immediately-eye-catching artifacts, and generally has taken place somewhere else, leaving a museum-goer without even a bare spatial context within which to imagine the action. Gallipoli tries hard to give some of that context, with 3D maps, models, first-person accounts, footage and photos (some rendered in 3D) and interactive elements.

Artifacts are often positioned within the walking space, which I think helps them be noticeable among the flashier visual elements.

One of the most effective features is a screen that demonstrates the effect of various weapons on the human body. The viewer selects which one and the skeleton takes the hit.

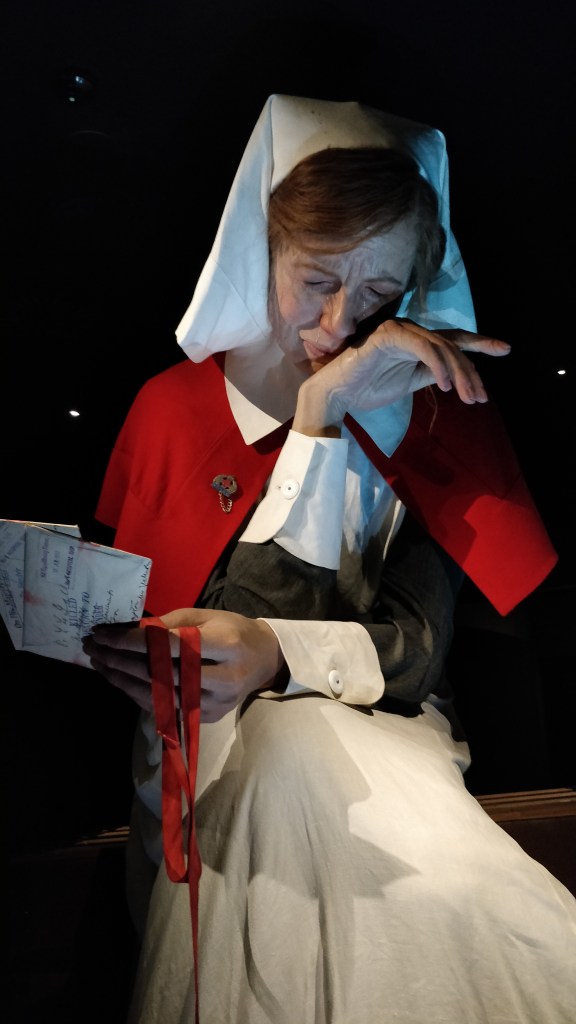

The interactive parts are very well done, and of course there isn’t much in the way of emotional relief throughout the space. While all of the various types of elements are represented throughout the viewer’s walk, the experience is anchored in the statues of the people whose stories make up the narrative of the exhibit, and really, those statues are extraordinary in their detail.

Conditions at Gallipoli were absolutely awful in just about every way. How awful? This awful:

And finally, as you leave, there is one more figure–surrounded by paper poppies left by other visitors–that serves as a stark reminder that this campaign was early in the war and many other hells awaited.

Again, the subject matter of Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War cannot be uplifting. I have always had some trouble with writing up exhibits that document the worst of humanity (long-time visitors to this blog might have noticed that I never did write about the ESMA in Buenos Aires). Regardless, Gallipoli is remarkably well done. It is well worth the visit to Te Papa, which is itself a wonderful museum. The exhibition is free (as is entry into Te Papa), and open every day except Christmas.