If you are lucky enough to find yourself on Rarotonga, the big island of the Cook Islands, you will find a pace of life altogether unfamiliar to anyone who was not brought up in Rarotonga, or similar locations. I personally was raised, lived, and vacationed in expansive places and had never been to anywhere as small and geographically isolated. It took me 45 minutes to drive the entire circumference of the island, and it only takes that long because the speed limit is 40 kph. So if you’re on this enchantingly beautiful rock in the middle of Absolutely Nowhere, Pacific Ocean, and you would like to visit Te Ara, you literally cannot miss it.

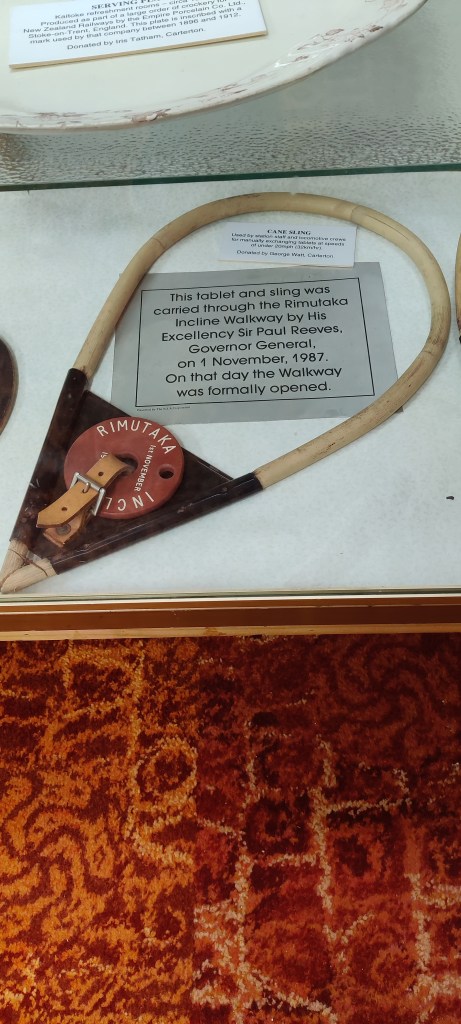

Te Ara serves multiple purposes for its community, one of which is a museum of Cook Islands history. And that history starts out roughly 3000 years ago, as Polynesian explorers working their way through, and I cannot stress this enough, an near-entirely empty Pacific Ocean found Rarotonga. Those navigators did that sort of thing with canoes and stick charts. I cannot get around a city I have lived in for four years without Google Maps.

There are examples of traditional garments on display, and also this modern creation, worn by Alanna Smith, 2016 Miss Cook Islands, based on the warrior Aketairi, from the island of Atiu:

Beyond these exhibits you get to the post-European contact period, and we all know how that goes. It’s a pretty reading-intensive set up, but not overwhelmingly so.

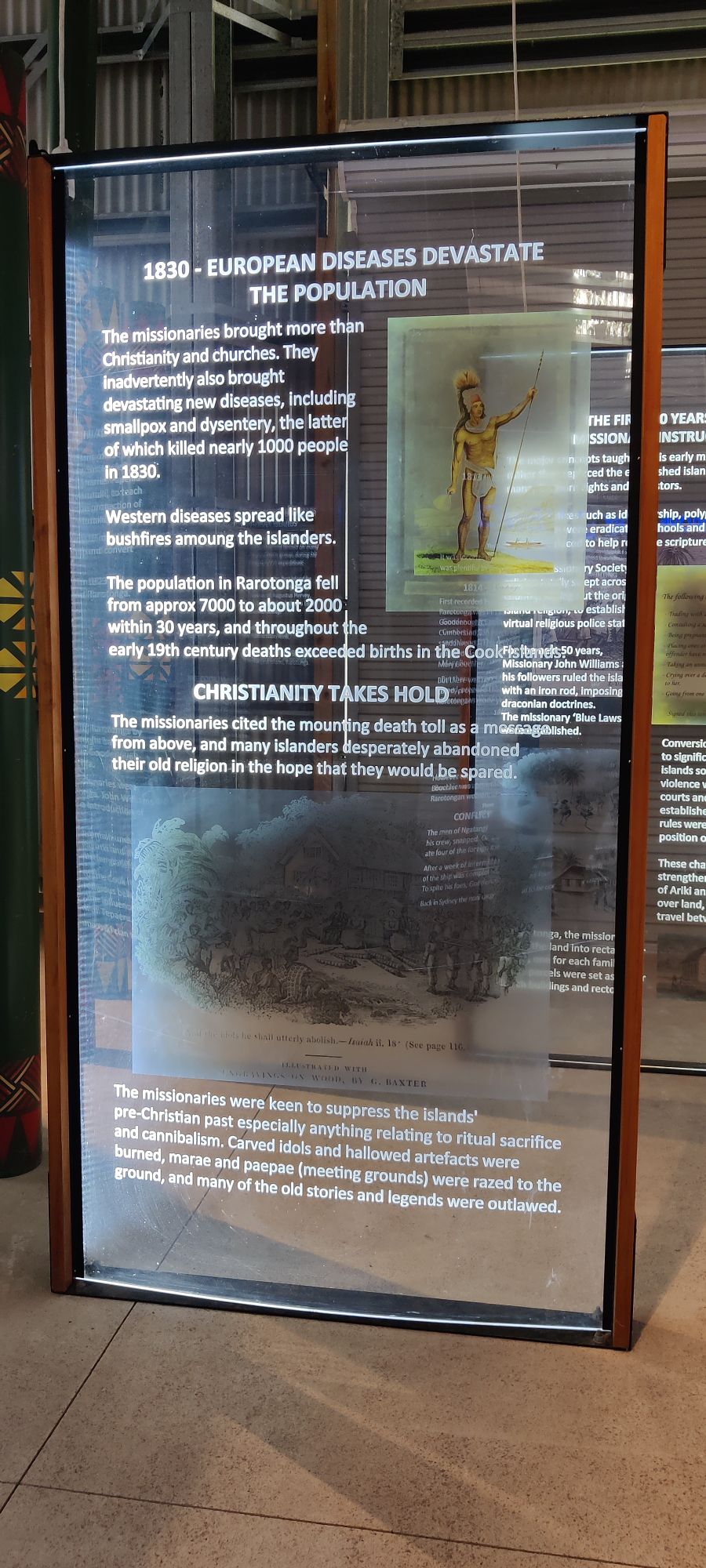

The arrival of missionaries and prolonged European contact in 1821 spurred a seismic upheaval in life. As it does. The diseases decimated the population, and the local practices and worldview were overwritten. The London Missionary Society had no chill.

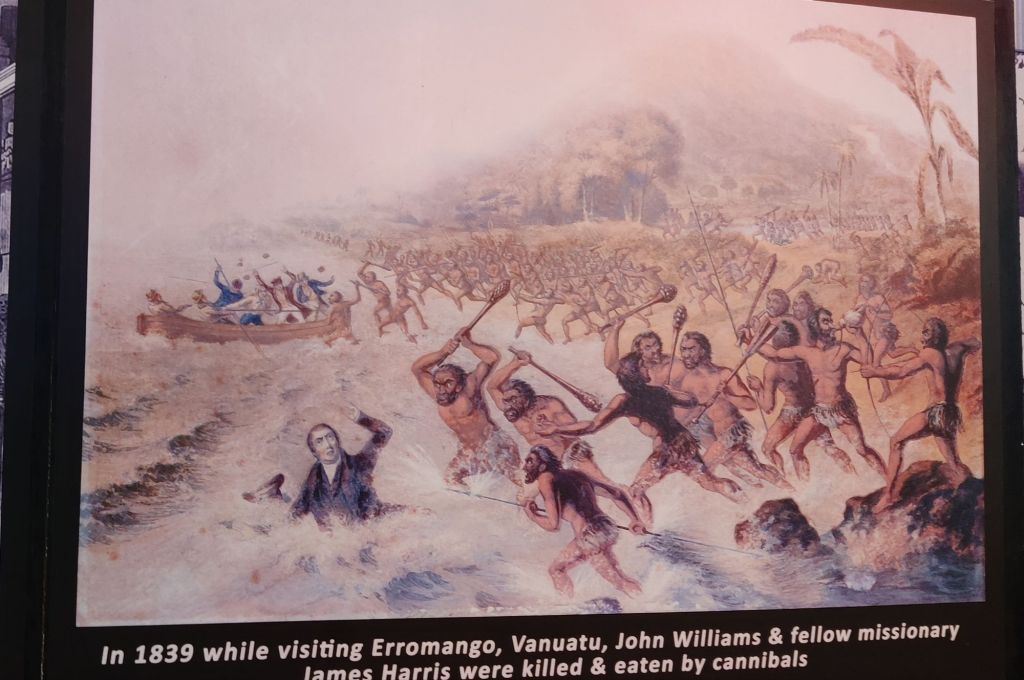

I vaguely recall (I was there some months ago now) that women’s lives were marginally improved under the new religion, although 19th century Christianity wasn’t great on that front in general, and everything else it brought was objectively terrible. This is the depressingly familiar pattern, but I mention it because the museum also has this illustration, whose blasé caption sort of off-handedly remarks on the end of missionary ruler John Williams’s adventures.

The exhibit continues through Cooks history up to contemporary times, as the political changes it’s undergone are marked in part via the changing of the flag through the years.

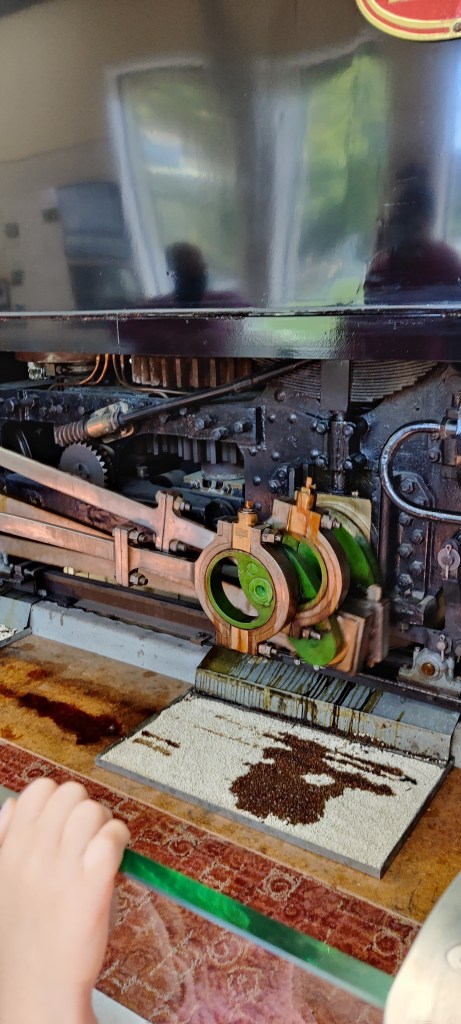

The Cooks are dependent on tourism, environmentally double-edged blade that it is, and are incredibly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The country’s challenges, environmentally and economically, are manifold and complex. In that vein, Te Ara includes some displays on the local ecology and its protection, as seen here in this tank demonstrating reef regeneration, at the end of your walk through the building.

Te Ara is a fine way to spend a few of your non-snorkeling hours on Raro, and being open daily from 9am (10am on Sundays) to 3 pm makes it one of the most open places there is (when I say life moves different in the Cooks, I mean it). There’s also a small café and store with locally produced goods.