The Museo de Patología was the first museum established within the University of Buenos Aires, in 1887. The first specimens came from the medical school hospital, and later, small collections from other hospitals were incorporated, making the museum an interesting piece of heritage for the medical school.

Sooooooooo…..

This museum is really a collection of specimens in jars. Like, body parts. There were so many fetuses, you guys.

As you might imagine, the museum has a notice posted admonishing visitors to consider the collection a place of learning and reflection and not a freak show gawk fest. Understandably then, photographing the specimens within is not permitted, and I did respect that. But holy shit there are people who did not and so there are photos available on Google Maps. They don’t include what were grimmest for me personally, so yay?

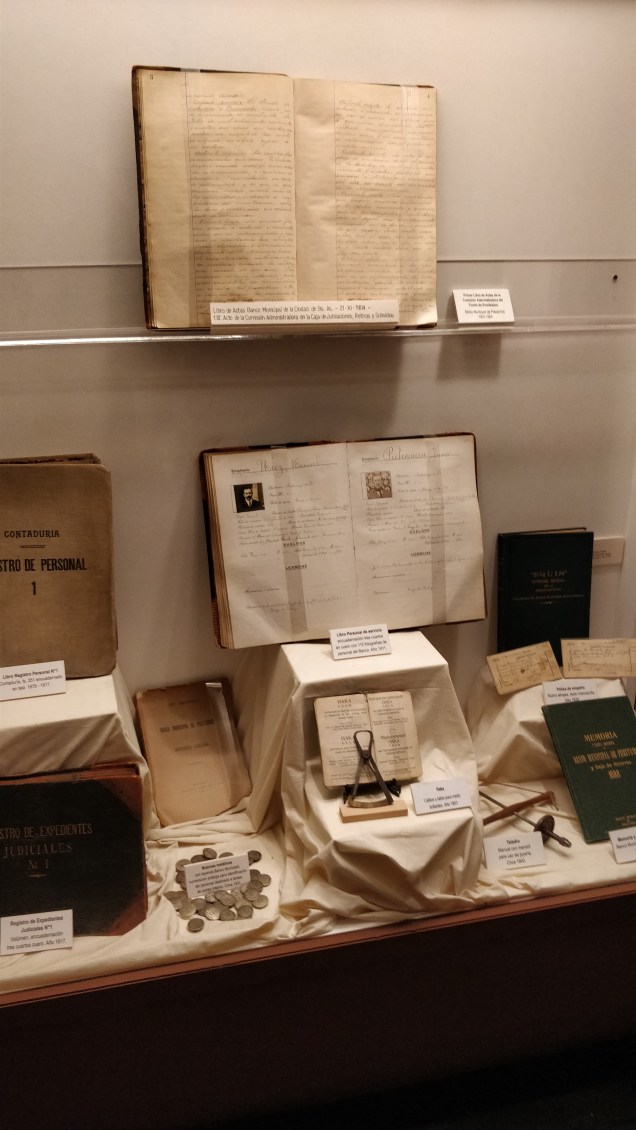

The museum is tucked away on the third floor of one of the UBA’s medical school buildings. You can just walk in, sign in, deposit any backpack you might be carrying in a locker and continue to the collection. Before you enter the actual zone, you might take a look at the exhibits they have outside the door.

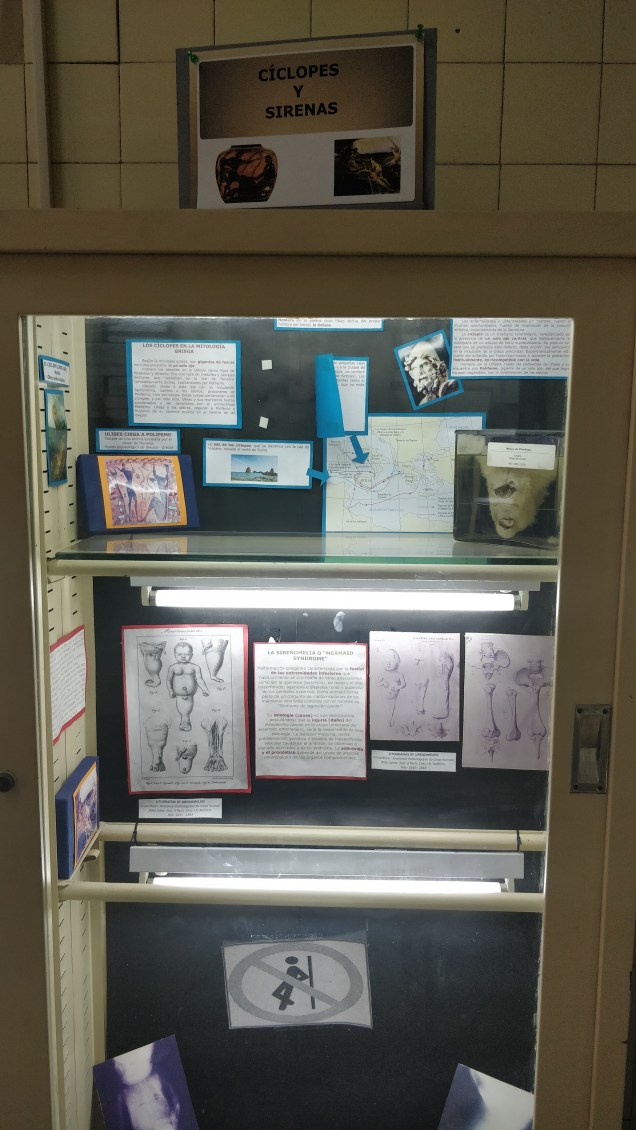

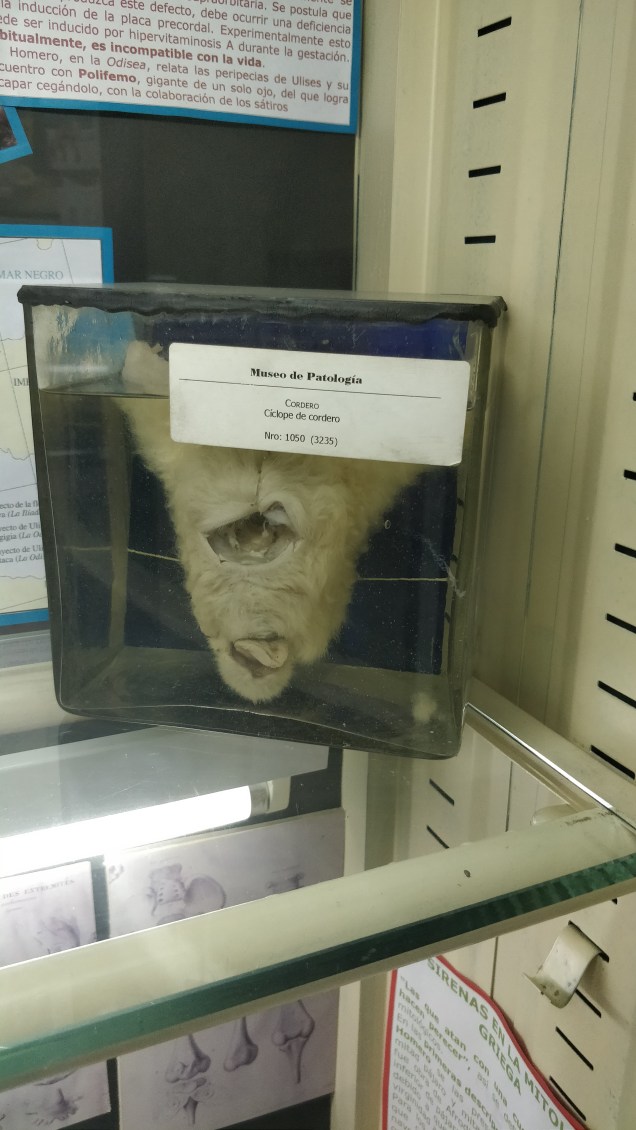

These exhibits have a few of the milder specimens, and give some information about the pathologies involved. If you’re disappointed by the lack of a human specimen example for mermaid syndrome, don’t worry–you can find one inside, you absolute lunatic.

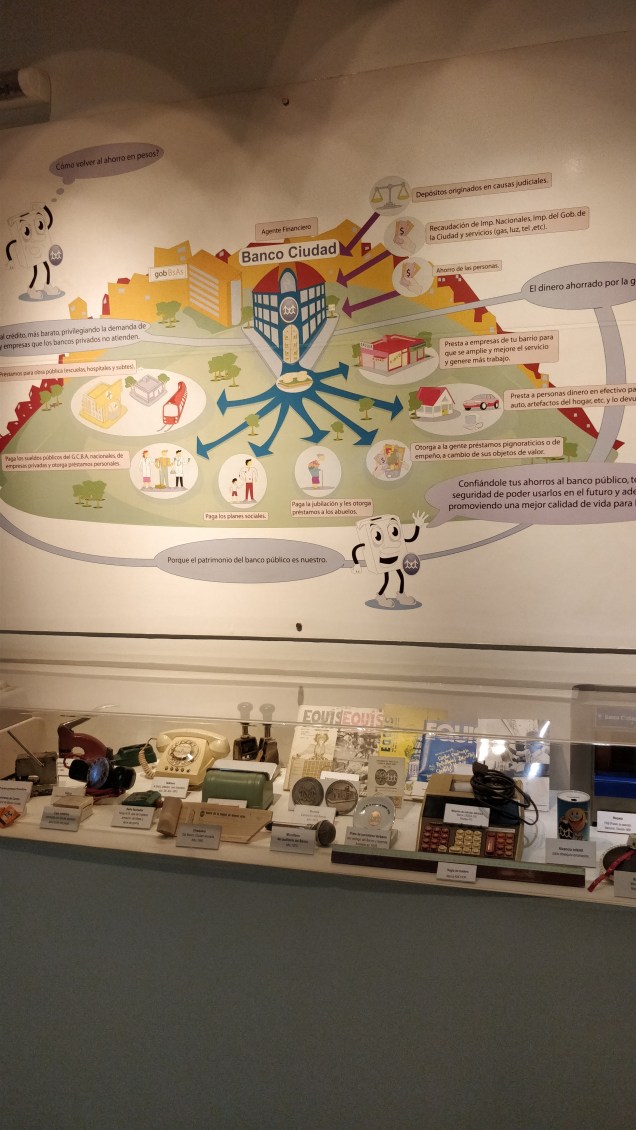

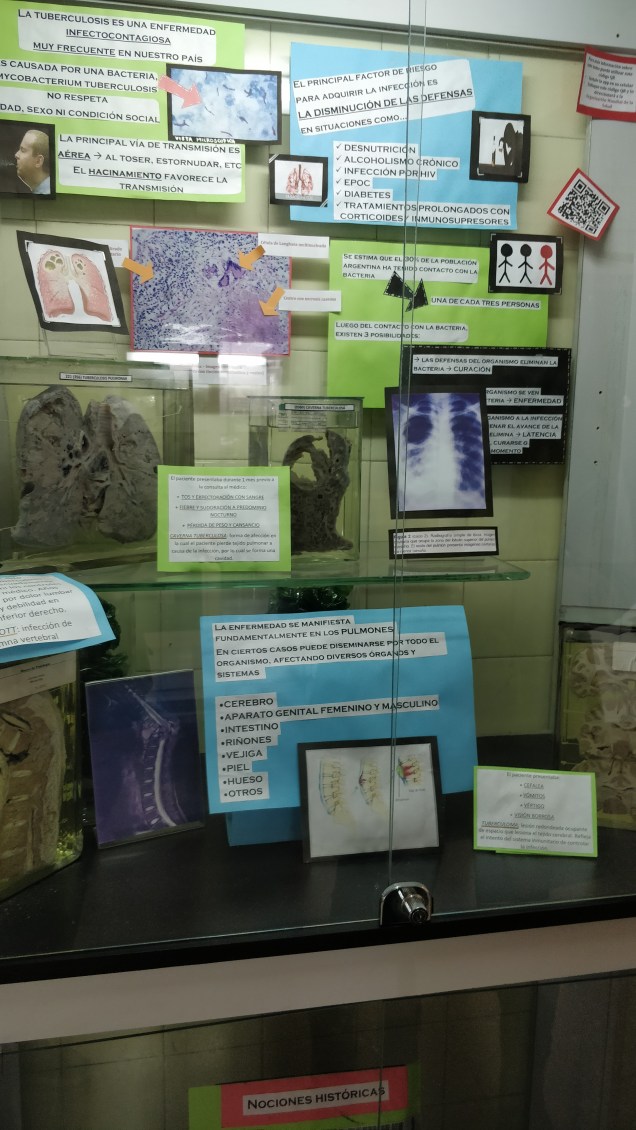

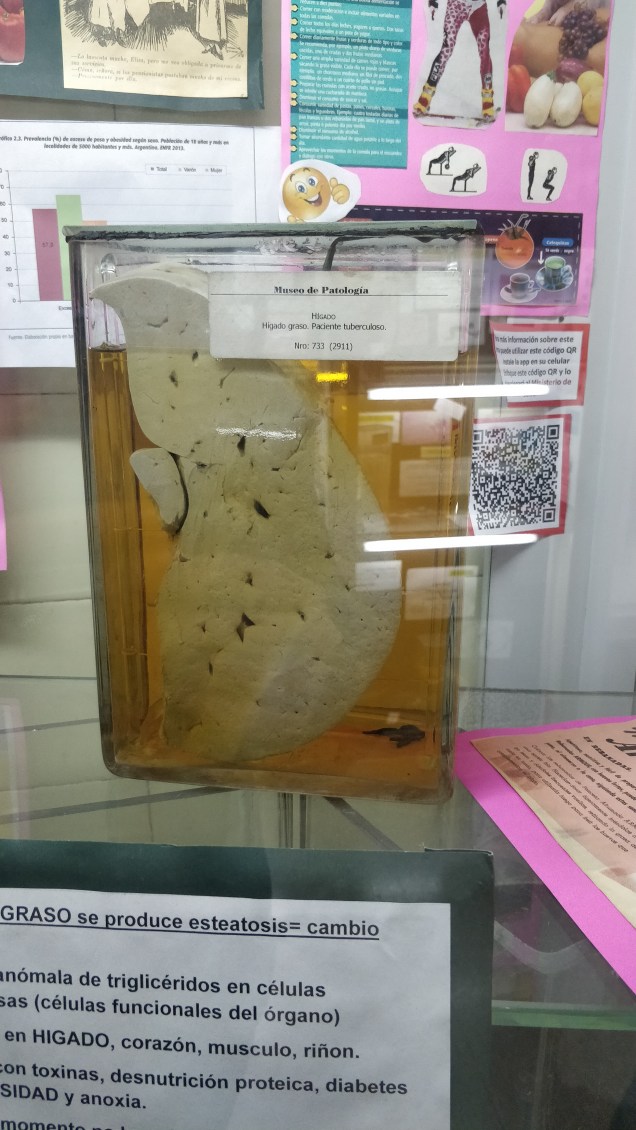

Ever wonder what the effects of tuberculosis look like on the inside? You are in luck, buddy.

This case explains that tuberculosis is a common infection in Argentina; one in three people have come into contact with the bacteria. There are three possibilities in case of contact: the body fights it off completely (ya good), the body doesn’t fight it off (ya sick), or the body fights it off just enough to prevent symptoms but not eliminate the bacteria (ya latent). It lays out the risk factors for developing the disease, and now you can lie awake at night, contemplating the fragility of the human condition.

This here is a fatty liver.

The display on liver health includes very helpful emojis. While that might seem a bit jarring juxtaposed with actual diseased human organs, I actually appreciate the effort made to communicate the information visually and clearly. Science museum exhibits are introductions, not text books.

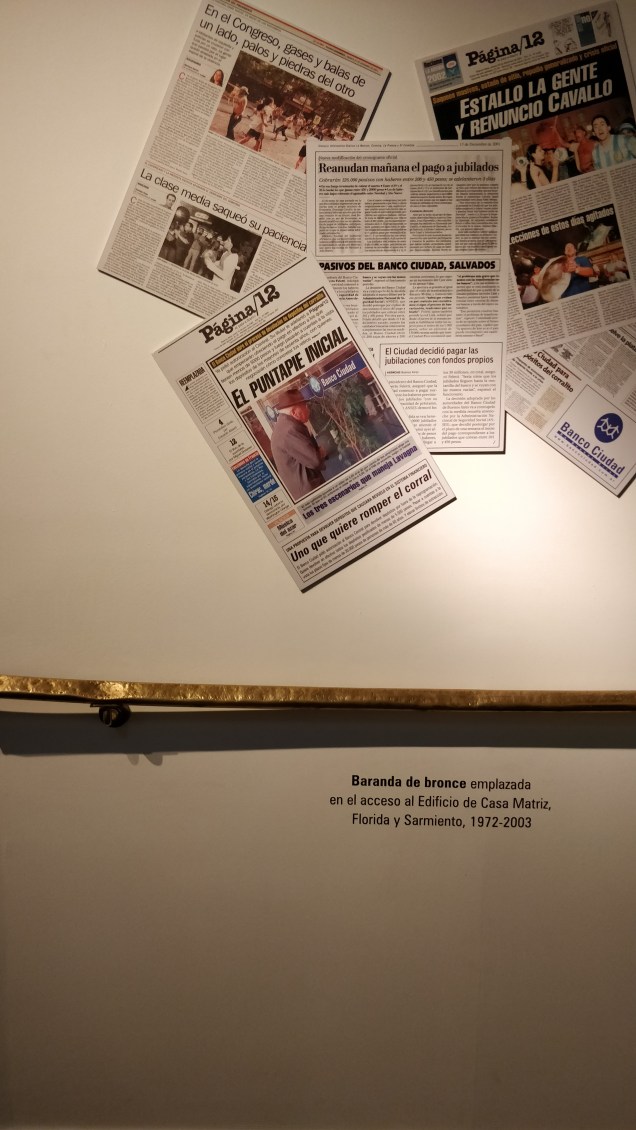

Inside, the museum is apparently undergoing a bit of a renovation, although what that entails isn’t clear; presumably the jugs of formaldehyde on the floor will at least get a cabinet during visiting hours. The whole museum is two large rooms, one upstairs and one downstairs, crowded with shelves and shelves of specimen jars grouped by pathology. The labeling is minimal, and includes no context information. This didn’t really bother me–aside from making it a collection for a highly specific audience that does not include me, museum-going boob Jo Public–until the tattoos. There are several pieces of skin (and one entire hand) displayed specifically for their tattoos. My exceedingly-chill-about-going-to-see-corpse-pieces friend and I estimated, based solely on a couple of dates included in the tattoos themselves, that they were probably around 100-125 years old. We also assumed they came from indigent patients at the medical school hospital. However, there is nothing to really confirm this in the labeling. There were a couple that seemed to have belonged to a sailor (sailors?) that had an anchor and the USA and Norwegian flags. There were a couple of examples of basic line drawings of circus performers, like a trapeze girl (boobs out) and a strong man. The subject matters also seemed to bear out our extremely rough idea of their age and origin. Tattoos are not a pathology, so the lack of context here was galling. I really, really wanted to know how old they were, who they belonged to, how they came to be preserved. This was easily the most interesting part of the collection, for me. As a museum that specifically includes the public in its mission, it would be nice for it to have more explanatory and educational displays. A cohesive exhibit about the history of the museum would be very cool, too.

Aside from all the jars, the museum also includes a historical library of pathology books in various languages as well as historical laboratory equipment. It is, as I mentioned, open to the public, but if you’re bothered by preserved body parts (think torsos and heads, not just organs and tissue), it’s best to give it miss. There is no signage in English, and since using your translation app is easily mistaken for photography, you’re on your own if your Spanish is terrible. The museum is located in a medical school building a couple blocks from the D subway line. It’s open Monday through Friday from 2pm to 6 pm, and it is free.